Since seven regional Hydrogen Hubs were selected by the Department of Energy (DOE) back in October, hub developers have been working on plans to establish successful regional networks of hydrogen producers, consumers and connective infrastructure.

As we’ve written before, hubs only stand to be successful if they closely engage and partner with local communities to mitigate potential harms and ensure that projects deliver positive outcomes specific to the communities in which they reside — a key objective of EDF’s BetterHubs. This is critically important for communities where residents are economically disadvantaged, historically marginalized, and/or people of color. These communities face legacy pollution and health problems, and they often lack adequate infrastructure and access to good health care. When severe storms, flooding or other climate-related impacts are put on top of these issues, they become threat multipliers, increasing the risk of severe health and economic impacts.

Ultimately, the hubs are operating in the context of existing communities with lived experiences, vulnerabilities and aspirations — and everyone involved with the hub projects must understand those factors, actively incorporating them in planning and throughout the project duration. A tool released by EDF and Texas A&M University, the Climate Vulnerability Index, can offer key data on the “vulnerability” piece of that context and help inform vital community engagement conversations.

Here are some insights that communities and hub developers can gain from the tool.

About the Climate Vulnerability Index (CVI)

Launched last fall, the Climate Vulnerability Index takes a robust, data-driven approach to understanding local drivers of vulnerability and shows how cumulative impacts can shape a community — from quality of housing and access to supermarkets to proximity to toxic waste sites.

While the main purpose of the CVI is to help users see which communities face the greatest challenges from the impacts of a changing climate, the data can also be helpful for Hydrogen Hub developers and communities in understanding existing vulnerabilities and threats at a neighborhood scale. The tool looks at intersections between growing climate risks and pre-existing, long-term health, social, environmental, and economic conditions.

To demonstrate the types of insights that the CVI can provide, we used it to analyze communities in and around the Mid-Atlantic Hydrogen Hub (MACH2), one of the seven awarded hub projects.

What the CVI can tell us about the Mid-Atlantic Hydrogen Hub

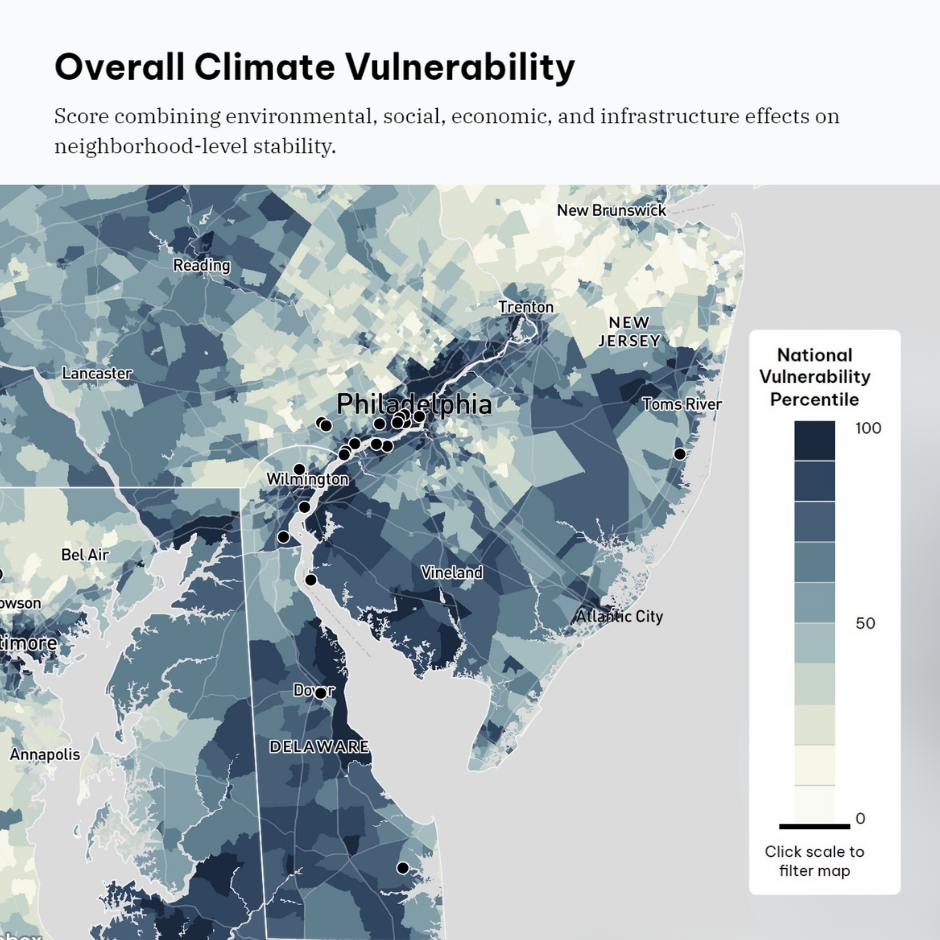

The MACH2 plans to connect hydrogen producers and consumers throughout Delaware, Southern New Jersey, and Southeastern Pennsylvania. Analysis is helpful for stakeholders to understand potential project impacts, and it can yield valuable insights about unique local factors that need to be considered in development plans. However, it’s crucial to acknowledge that the analysis that follows is built upon the limited Hub-related information thus far provided on MACH2 facilities. We expect much of this to evolve moving forward.

The following map highlights where production and end-use facilities along with pipelines and connectors will be potentially sited, shown as black points. They are overlaid on a backdrop of the Overall Climate Vulnerability Index, where darker colors indicate higher vulnerability.

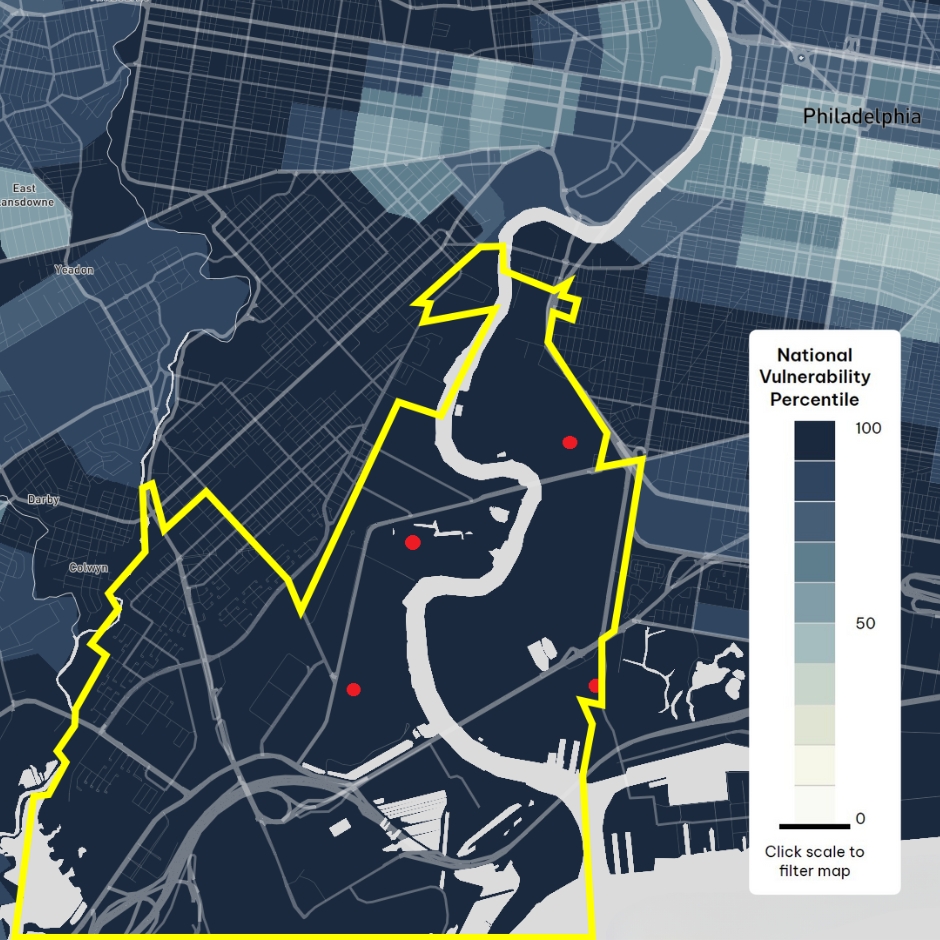

From this regional viewpoint, we will take a closer look at Philadelphia, where the highest concentration of facilities has been proposed. Four facilities have been provisionally slated for development in and around Eastwick, a low-lying neighborhood in the southwest of Philadelphia. This area, outlined in yellow, has some of the highest overall vulnerability scores in the U.S., driven by long-standing inequities that shape its resilience to climate impacts and may affect its exposure to development projects.

Eastwick community vulnerabilities: a history of pollution and flooding

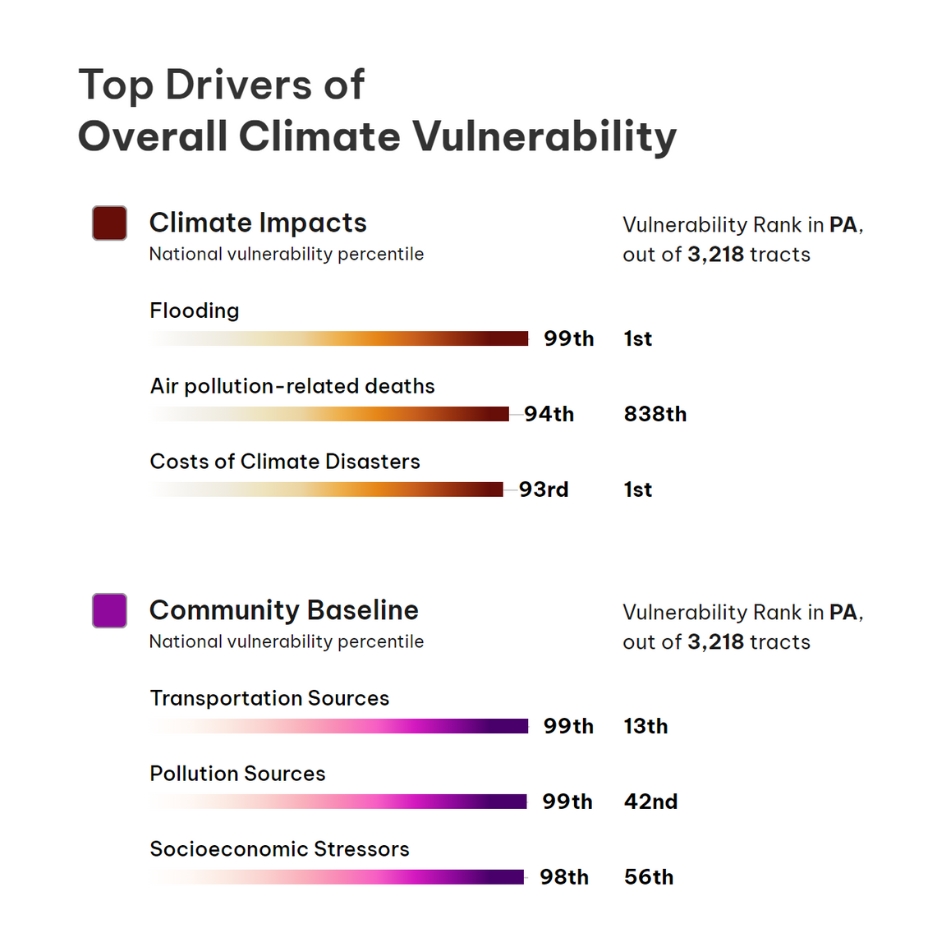

Eastwick possesses high vulnerability scores for pollution sources, ranking in the 93rd to 99th percentiles for the nation. ‘Pollution Sources’, as a CVI category, includes facilities that generate, manage, or burn hazardous waste; facilities that make or process chemicals that pose significant human health risk; Superfund sites; and more:

- A notable pollution source for Eastwick was once Clearview Landfill, which the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) declared as one of the most contaminated Superfund sites in the country. After eighteen years of advocacy by hard-working community advocates, like the Eastwick Friends and Neighbors Coalition, the local community achieved a victory when the EPA began remediation of the site. Local leaders attribute the project’s success to the agency’s integration of their community advisory group into the planning process — an example of how close collaboration between a federal agency and impacted communities can bring about success.

With these vulnerability scores comes a concerning history of pollution for the community:

- A failed Urban Renewal project displaced thousands of Eastwick residents in the 1950s and rebuilt the neighborhood on top of unsettled soil and in flood prone areas. The project was never completed, and there are still swaths of undeveloped land that attract dumping, which the city struggles to address.

- Up until 2019, Philadelphia Energy Solutions (PES) refinery, the largest and oldest refinery on the East Coast, processed the cancer-causing chemical benzene before it shut down following multiple explosions and a fire. In the explosions, hydrofluoric acid, one of the deadliest industrial chemicals in use, was released into the atmosphere, and the force of the explosion sent a bus-sized piece of debris flying across the river.

- Earlier this year, a pipe ruptured at Trinseo PLC, a chemical plant upriver of Eastwick in Bristol, releasing 8,100 gallons of latex finishing material that flowed down into the Delaware River.

The predominately Black neighborhood of Eastwick has faced more than a century of industrial development and pollution:

- Industrial facilities, regulated by the EPA, within three miles of the neighborhood have had a number of air, soil, or water violations and/or enforcement actions.

- Interstate-95 runs along the southern outskirts of the area, exposing residents to deadly air pollution that makes them more vulnerable than 82% to 89% of all other census tracts in the U.S.. This exposure impacts child and maternal health in particular.

Eastwick also experiences flooding risks that have the potential to aggravate environmental harms. Its census tracts rank in the 92nd and 99th percentiles for flooding — this community is more likely to experience flooding than almost every other census tract in the U.S.:

- The area is threatened by higher storm surges due to sea level rise from the nearby Delaware River and a tidal section of the Schuylkill River.

- More intense and frequent storms also swell the volume of two creeks that converge in the neighborhood, making it prone to chronic flooding.

- Residents are concerned that repetitive catastrophic flooding could also bring toxic materials into residential areas. More recently, Philadelphia International Airport announced it was expanding its cargo business onto 120 acres of the surrounding floodplain, which many fear will make both the airport and surrounding areas more susceptible to flooding.

What this means for Hydrogen Hubs

As this initial MACH2 analysis shows, the CVI can help create starting ground for community-led discussions and negotiations by providing actionable data to back up the lived experiences of community members. And it can help developers come to the table with a greater understanding of the risks and history faced by communities, enabling discussions to focus on ensuring community benefits and avoiding the same mistakes from past oversights.

For example, for MACH2 stakeholders and surrounding communities, the flooding insights may aid in conversations around how they responsibly, equitably and efficiently site hub operations — ensuring they address the risk of building in a flood plain in risk management plans. Or, when it comes to discussions around tracking and mitigating local environmental impacts, the data on Eastwick’s history of air pollution may help highlight the need for zero-emissions transportation to and from the hub that supports healthier air quality.

Ultimately, nothing will trump the value of direct engagement with members of the community — tools and analyses cannot substitute for that. Learning from their lived experiences, developers can understand the risks and rewards that a community may face with developments, a vital step toward realizing Hydrogen Hubs that bring about beneficial outcomes for both communities and the environment.